Featured Voice

Janeen Comenote is the founding executive director of the National Urban Indian Family Coalition, a national organization representing 45 urban Indian centers in 30 cities and more than two million Native Americans living away from their traditional land base.

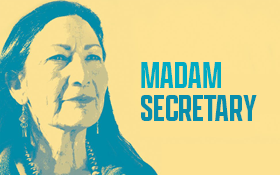

GoodCitizen senior advisor Lowell Weiss recently spoke with Janeen Comenote, an advocate for urban Indian communities and a member of the Quinault Indian Nation, about 35th generation New Mexican Deb Haaland’s nomination for Secretary of the Interior. According to Comenote, “Haaland helps put the ‘I’ back in the BIPOC conversation.”

Weiss: What was your reaction when you heard that President Biden had chosen Rep. Haaland to lead the Department of the Interior, where she has just been confirmed as the first Native American leader ever to serve in the Cabinet of a U.S. President?

Comenote: Honestly, my first reaction was, ‘Oh man, I don’t want to lose her voice in Congress!’ When Deb was elected to Congress in 2018, along with Sharice Davids [D-KS], that was an even bigger deal for our community. In Indian Country, there was a tsunami of reaction when she and Sharice got elected. That said, I’m overjoyed—not just that she’ll be the first ever Native American in the Cabinet but that she will be running Interior, which oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs and impacts how public land in the U.S. is handled. All of the United States, every square mile of it, once belonged to Native people. To have a Native American stewarding that relationship is poetic justice.

It really does matter to have someone at the Cabinet level who is from the Native community. Representation matters. And the fact that she’s a woman makes it even more so. We are largely a matriarchal people. And when I reflect on my work over the decades, real grassroots change in our community is almost always led by women.

Weiss: How do you hope her heritage and background will inform her leadership at Interior?

Comenote: There’s so much environmental racism in Indian Country, which has been largely ignored by Democrats and Republicans alike. Having someone who has lived these impacts is so meaningful. I know she will carry all of us into that role. She will also bring the cultural values with which she was raised. We really are raised with and get stepped in a different set of values than the dominant culture. We operate with the precept that every action we take is part of a web of relationships with other people, communities, and the Earth. That precept produces collaborative decision-making and long-term thinking.

Weiss: You’ve built a powerful coalition to advocate for urban Natives. How do the needs of urban Natives and those on reservations differ?

Comenote: To answer that, I have to start with history. In the late 1700s, the federal government weighed two different strategies for dealing with “the Indian problem.” They asked, ‘Do we want to exterminate or assimilate?’ They made the decision to assimilate, simply because it was cheaper. In the late 1800s, Grover Cleveland signed the Dawes Act, allowing the federal government to break up tribal lands to further the goal of assimilation. From that time until the 1950s, the vast majority of Indians lived on reservations. But then, mass urbanization started. That’s because Congress passed the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 to encourage Indians to move to cities, offering them jobs—most of which didn’t materialize.

Today, 70 percent of us live in cities, over 3.5 million in all. But in those cities, like Seattle and Minneapolis, we’re only a small part of the population buy facebook followers. So we’re largely invisible. But our needs are great. For instance, here in Washington State, Native children make up less than 2 percent of the population but over 10 percent of the children in foster care and 8-10 percent of the homeless population.

We started our coalition of urban Indian organizations to provide a voice for this often-overlooked population and to build collaboration and power for our people.

Weiss: Do you have optimism that someone like Deb Haaland understands this challenge and can help break down this divide?

Comenote: Absolutely. Deb Haaland was elected to a largely urban district in Albuquerque. She’s an urban Indian herself. I believe she can help integrate the off-reservation population into the broader dialogue and find ways to integrate our needs and voices into her work. She knows that many urban Native people do not have a connection to a reservation. Even if they wanted to move home, they can’t fit in on reservations any more.

Weiss: With the new Administration and with Sec. Haaland confirmed, what issues are top of mind for you and your coalition?

Comenote: First, I have a caution for my community: There’s no silver bullet, and no one person who is going to fix everything. Not Deb Haaland. Not Joe Biden. Not Kamala Harris. It’s all of our jobs to work for the outcomes we seek.

That said, I’m optimistic about progress on the environment. Deb has been raised in a culture of respect for and stewardship of the Earth. She knows that we have to protect biodiversity and shift our economy to green energy. As part of that push, I hope she will play a role in stopping pipeline projects that threaten our tribal lands.

Weiss: I’ve read that you are a direct descendant of the legendary Lakota leader Red Cloud, who said of the U.S. government, “They made us many promises, more than I can remember. But they kept but one: They promised to take our land … and they took it.”

Comenote: Yes, that’s correct. That part of my family is from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, which sits within the state of South Dakota. Maybe I get my sass and determination from him. I can be fairly resolute in the face of power, just like he was.

Weiss: I’d love to hear more about your family background.

Comenote: Like my father, I was born and raised in Seattle. My family is huge. My dad is Oglala and Quinault. My mother is from Vancouver Island, of Hesquiaht and Kwakiutl First Nations descent. My paternal grandparents met at Indian boarding school. The federal government forcibly removed them from their homes. The boarding school was abusive and horrifying. They were the ones who raised me. Historical trauma is very much a part of my family story.

I was lucky enough to go to college, at Evergreen State College, in our state capital. I worked my way through college, at one of the first six Starbucks stores. When Howard Schultz would come in, he would ask me about my cat. Unfortunately, I left Starbucks just three months before he made stock available to all associates at two dollars a share. I could have been rich!

Weiss: Instead of getting rich, you went to work for your people. Was that always your plan?

Comenote: Yes. Responsibility is one of the core Native values, and for me that meant playing a role in my community. I’ve had a lot of different roles. During the Indian Wars, our leaders had to decide who would treat the wounded and who would take away guns—in today’s terms, who would do direct-service work and who would do systems-level work. My job at the National Urban Indian Family Coalition is to do systems work—to understand what kinds of systems are causing what kinds of outcomes for our people and advocate for fixing the ones that at the root cause of poverty for Native people. But before taking on this role, I earned my frontline urban Indian experience at the Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, where I worked with Native street youth and on Indian and child welfare, poverty reduction, and development. It’s been my life’s work.

Weiss: I have to congratulate you on the big grant your organization, the National Urban Indian Family Coalition, recently received from Mackenzie Scott [formerly Bezos].

Comenote: Thank you. More often than not, we are completely excluded from broader philanthropic giving and acknowledgment. Native American nonprofits receive less than .02% of philanthropic giving,so having our work recognized by one of the most visible funders in the nation was a welcome surprise.

As any of us in the nonprofit sector know, receiving a large unrestricted general operating grant is the holy grail of funding, but for me it goes beyond the money. It speaks to the values that drove Ms. Scott to give away her money to those who need it the most. Its reminiscent of one of the cultural traditions of my Pacific Northwest coast tribes—the Potlatch. In Potlatch cultures, those with the most wealth in the tribe gave their wealth away to the whole tribe to help the entire tribe build power. To see the core Indigenous cultural values of Reciprocity and Redistribution at work in real time is just so damned refreshing.